Put Back Spread

Risk: low

Reward: moderate

General Description

Entering a put backspread entails selling a higher strike put and buying more lower strike puts (same expiration month). It's the same as a long put ratio spread except the ratio of long puts to short puts is not locked at 2:1; it could be 3:1 or 4:1 or whatever you want.

(draw a put backspread risk diagram here)

The Thinking

You're bearish and believe the underlying stock has big downside potential. But instead of using a long put strategy, which has high cost of entry, you use a put backspread, which has a much lower initial cost (possibly a net credit) but still has unlimited profit potential. Essentially you are using the proceeds from the short put leg to pay for the long put leg. If you're wrong and the stock drops, you won't lose much, if anything, because as an added bonus, depending on how the trade is constructed, you may be able to initiate the trade for a net credit.

Example

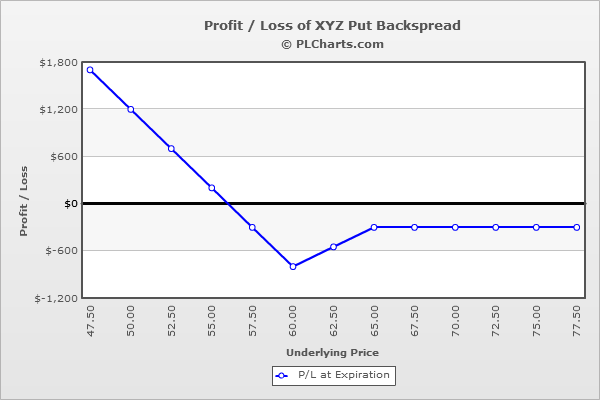

XYZ is at $62.00, and you are confident the stock has big downside potential – so big you are willing to roll the dice with out-of-the-money puts – but you’d like to lessen the loss incurred should the stock rally. You buy (3) 60 puts for $3.00 each and sell (1) 65 put for $6.00. The net debit is $3.00.

Above $65, all puts expire worthless, and your loss is the net debit paid when the trade was initiated.

At $60, your max loss occurs. You lose money on the long puts (you bought then for $3.00, now they’re worthless) but make a little in time decay on the short put (you sold it for $6.00, not it’s worth $5.00). So the total loss is $8.00.

Below $60, the profit from one of your long puts will be canceled out by the loss of the short put, but you’ll make money point-for-point via the other two long puts (once the stock is below breakeven).

Compared to a long put, a put backspread gives you some upside protection, but your downside is reduced, your breakeven level is less favorable and your loss, should the stock not experience a big move, is greater.

The PL chart below graphically shows where this trade will be profitable and at a loss.

|